Having lived now in the American Southwest for a substantial amount of time my regular readers know of my interest in Native America. In the westward expansion of the United States Native Americans were treated almost as badly as any indigenous group anywhere in the world. It has surprised me how well they have adapted to the dominant Anglo world and still been able to retain their own cultures.

|

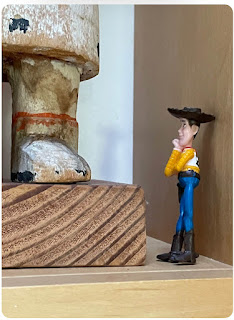

| Anglo contemplating Hopi Katsina Doll |

You may have heard of “unceded land”. It means that the American Indians and First Nations (as the Canadians refer to their Indigenous people) never ceded or legally signed away their lands to the government. This fact has been recently admitted in statements like the bronze plaque The Metropolitan Museum of Art added to its façade on May 11, 2021, which acknowledges the homeland of the Indigenous Lenape diaspora.

It follows that tribal cultural property is also not individually owned but held in trust by an authorized Native American caretaker or caretakers for the tribe as a whole. Under traditional tribal law, these caretakers have no rights to sell the property in their possession.

The United States has laws of recent vintage to protect Native American art and artifacts. The Archeological Resource Protection Act (ARPA), 1979, addresses taking or dealing in material from Federal or Indian Lands. Another is The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), 1990, which mandates the return of Native American human remains, therefore requiring archeological exploration before building on land that is likely to have had burial grounds. Additionally, NAGPRA establishes the right of repatriation from museums of sacred objects and those claimed as cultural patrimony taken from tribal lands. It also covers areas of unceded land that First Nations (read Native Americans) traditionally occupied. The United States and Canada, naturally have a great deal of land that qualifies.

Both laws cover roughly the same material requiring respectful treatment of human remains and returning them to an individual or tribe. They also cover “but are not limited to pottery, basketry, bottles, weapons, weapon projectiles, tools, structures or portions of structures, pit houses, rock paintings, rock carvings, intaglios” etc.

As I have said, none of this is simple. For instance, a Katsina is a spirit being in the religious beliefs of the Pueblo peoples. Small wood sculptures made in their image orginally served as teaching tools for the young but developed into collectibles for Anglos. For more information click on this link published by the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona that has one of the great collections of Native American Art. https://heard.org/katsinadolls/faq.html The museums in Santa Fe have collections of Katsina “dolls” but will no longer display them because some of the subjects are considered sacred. Still, there is no law preventing their sale by galleries and directly by Hopi and Zuni artists participating in various markets. Here you can see some of the Heard Museum’s collection on display. As this museum is in Arizona, it has not been subject to the political pressure of the New Mexico pueblos.

Misrepresenting works as Indian made, if they are not created by a Native American, is another matter and a problem for both artists and collectors. The 1990 Indian Arts and Crafts Act was passed by Congress to address the issue. However, it has proved difficult to enforce as can be seen by the number of misidentified offerings in certain Santa Fe tourist shops priced below authentic Indian works.

Needless to say, there are many different interest groups: those who keep the religion and history of the tribe, the artists from that tribe, the gallery owners and the collectors. This last sentence can be expanded into at least one chapter or a book, but the point is that it is always imperative to try to understand from where each constituency comes and then work to arrive at an equitable solution.